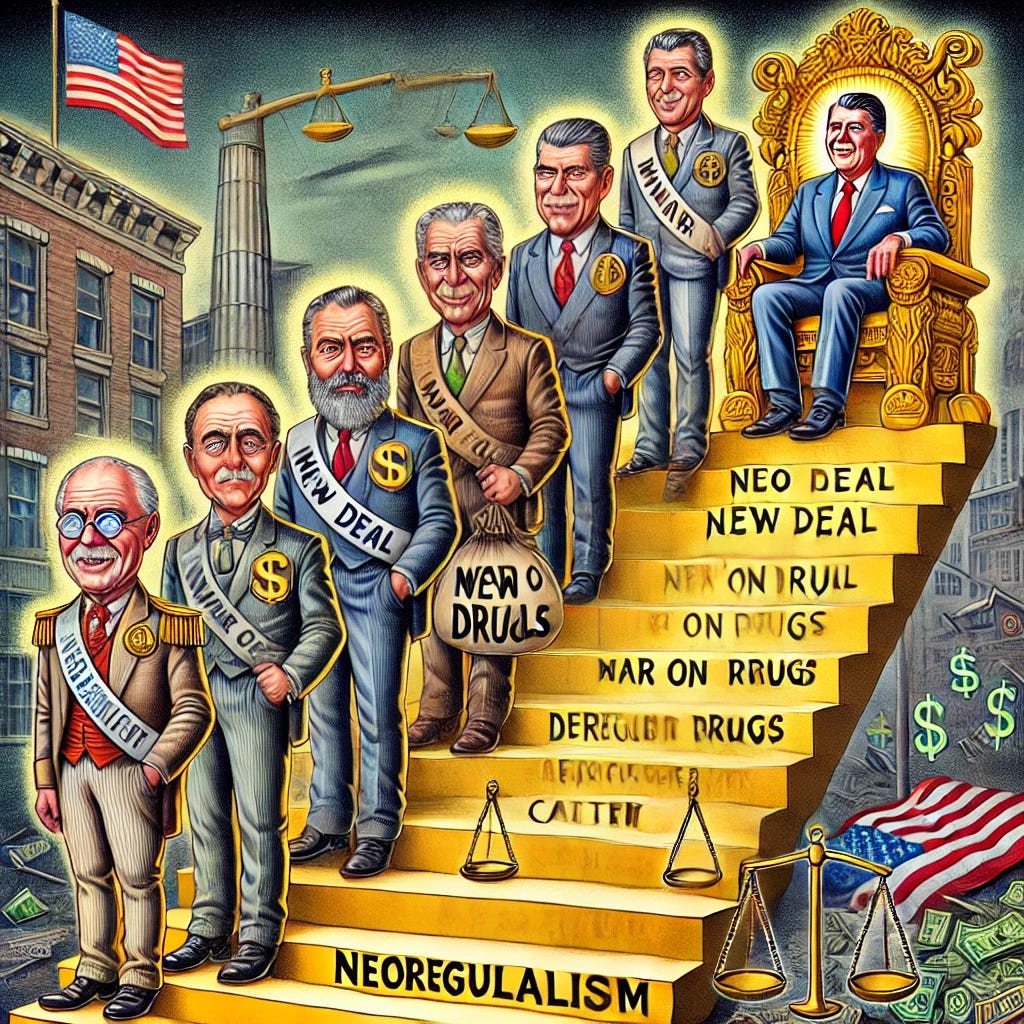

Reagan didn't create the neoliberal strategy change

Neoliberalism was introduced by small steps one after the other

It’s a common misconception that Robert Reich gives expression to that Ronald Reagan was the first U.S. president after Franklin D. Roosevelt to undermine the welfare state, the middle class, and public services. While Reagan indeed amplified these efforts, the groundwork for his policies had been laid by several presidents before him.

Harry S. Truman (1945–1953): Although Truman extended parts of the New Deal legacy, such as through his Fair Deal proposals, he also began shifting away from its core principles. His administration pushed anti-communist policies that laid the groundwork for McCarthyism, weakening unions and creating fear-driven loyalty programs that impacted working-class activism.

Dwight D. Eisenhower (1953–1961): Eisenhower maintained some New Deal policies but prioritized business-friendly economic growth. He supported large-scale infrastructure projects like the Interstate Highway System, which indirectly fueled suburbanization and economic inequality. His administration also began rolling back regulations on businesses, quietly introducing neoliberal ideas into governance. Eisenhowerwas a strong supporter of the military-industrial complex and ordered the assassination of the peaceful Robert Lumumba. Lumumba had helped free Congo from colonialism.

John F. Kennedy (1961–1963): John F. Kennedy's presidency blended elements of Keynesian economics with early traces of what might be called proto-neoliberal policies. On the Keynesian side, JFK championed significant fiscal stimulus, promoting government spending to drive economic growth and full employment. His administration emphasized policies aimed at boosting demand, including public investment and infrastructure development.

However, JFK also pursued measures that leaned toward favoring wealthier individuals and large corporations. He cut top marginal tax rates significantly, reducing them from a high of 91% to 70%, with the intent of stimulating investment and economic activity. This policy shift marked a departure from the more progressive tax policies of the post-war era. Additionally, his investment tax credits, designed to encourage business investment, disproportionately benefited large corporations, many of which used the credits to automate and increase profits rather than creating jobs or aiding smaller enterprises.

JFK’s presidency thus reflected a complex mix of progressive economic intervention and policies that laid the groundwork for more corporate-friendly economic approaches in the decades to come.

Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969): Johnson's Great Society programs expanded welfare and civil rights, but his escalation of the Vietnam War and reliance on deficit spending set a precedent for weakening social investments in favor of military priorities.

Richard Nixon (1969–1974): Nixon actively shifted the U.S. toward neoliberal policies. He severed the dollar's link to gold, paving the way for global financial deregulation. His War on Drugs, introduced in the 1970s, disproportionately targeted marginalized communities, fueling mass incarceration. Nixon also undermined unions and weakened the regulatory state while expanding executive power.

Gerald Ford (1974–1977): Ford focused on combating inflation with austerity measures rather than addressing unemployment or social inequalities. His approach encouraged further deregulation and prioritized business interests over public welfare.

Jimmy Carter (1977–1981): Carter is often seen as a moderate, but his administration embraced early neoliberal policies. He deregulated industries like airlines and trucking, which disrupted stable, well-paid jobs. His focus on monetary restraint and free-market solutions set the stage for the full neoliberal turn under Reagan.

Ronald Reagan (1981–1989): Reagan capitalized on decades of groundwork laid by his predecessors. He slashed taxes for the wealthy, dismantled unions, cut social programs, and aggressively deregulated industries. His administration marked a turning point in the acceleration of income inequality and corporate dominance.

Learning from History

The neoliberal transformation did not happen overnight. It was the result of decades of policy shifts and the erosion of public memory about the horrors of the Gilded Age.

The Horrors of the Gilded Age and the Roosevelts' Great Reforms

Imagine a time when a few super-rich people had almost all the money, while millions of families struggled just to survive. That was America during the Gilded Age, around the late 1800s and early 1900s. It looked shiny and rich on the outside, but underneath, things were pretty terrible for most people.

What Was So Bad About It?

Rich men, called "robber barons," controlled everything—oil, railroads, steel, and even the banks. They made sure no one else could compete with them. If someone tried to start their own business, the robber barons would crush it. Workers were paid very little, forced to work long hours in dangerous factories, and children as young as ten—sometimes younger—had to work in these places too.

The rich bribed politicians to make rules that helped them stay rich. For example, they made laws to stop workers from forming unions, which would have allowed workers to stand up for better pay and safer jobs. This corruption made the gap between rich and poor even bigger.

People who had recently immigrated to America were treated badly. Racist laws were passed to stop them from coming, and Black men, who had recently won the right to vote, were blocked from voting through unfair rules.

It was so bad that many families didn’t have enough food, while the rich threw huge parties in their mansions. The country’s democracy—where everyone’s voice was supposed to matter—seemed broken because the rich controlled everything.

How Did Things Change?

People finally had enough. Journalists, called "muckrakers," wrote articles and books showing how bad things were. Workers protested, and new leaders stepped in to fix things.

One of these leaders was Theodore Roosevelt, or "Teddy." He became president in 1901 and said, "No one is above the law, not even the rich." Teddy broke up the big monopolies—the giant companies that controlled entire industries—using something called the Sherman Antitrust Act. He also worked to protect nature, creating national parks to stop big companies from cutting down forests or mining everywhere.

Teddy’s fifth cousin, Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR), became president during another tough time in the 1930s. This was after a huge economic crash called the Great Depression, where many people lost their jobs and homes. FDR created programs to help regular people. He gave us Social Security, which still helps older people have money when they retire. He made rules so workers could form unions, work fewer hours, and get paid fairly.

Both Roosevelts reminded Americans that the country should work for everyone, not just the rich.

Why It Matters Today

The Gilded Age was a warning. When a few people have too much money and power, democracy starts to crumble. The Roosevelts showed us that strong leadership and laws can create fairness.

But we have to remember these lessons. Over time, some leaders slowly started undoing these reforms, step by step. By the time Ronald Reagan became president in the 1980s, many of the rules protecting workers, the environment, and fairness had been weakened.

To make sure history doesn’t repeat itself, we need to learn from the past, just like the Roosevelts taught us: fairness, democracy, and protecting everyone should always come first.

Just as reformers like Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt arose to challenge corporate dominance, today’s crises demand a reexamination of the systems that concentrate wealth and power. Understanding this history is essential to charting a course toward a fairer, more equitable future.

Ideas of inequality inherent in the origins of USA

Belief in the value of unequality has been a part of the United States from the very start. When America was still controlled by England, huge amounts of land were given to wealthy individuals, like Pennsylvania, which was granted to an English duke. This meant that ordinary people had little chance to own or share in the resources.

Later, many immigrants came to America seeking a better life. But if they couldn’t afford the journey, they had to work as indentured servants. They had to spend years working for almost nothing to repay their travel costs before they were free to start their own lives.

After America became independent, many of its economic ideas were influenced by Adam Smith, a famous economist. Smith believed in “free competition,” where everyone could compete freely in business. But this also meant that there were no rules to protect people from becoming very poor while others became extremely rich. This led to a lot of inequality, especially during the 1800s.

Before Adam Smith’s ideas became popular, many European countries believed the government had an important role in guiding the economy. They thought the government should create some kind of market rules, support skilled work, and focus on what was good for society as a whole. This approach, which Erik S. Reinert describes in his book How Rich Countries Got Rich … and Why Poor Countries Stay Poor, had helped Europe thrive for centuries by regulating markets and encouraging industries that required knowledge and skills.

Adam Smith, however, argued that all kinds of work were essentially equal, whether it was farming or something that required a lot of expertise. This made it easier for low-paying, low-skill jobs to dominate. This increased inequality and weakened the idea of investing in skilled labor.

In short, America’s focus on competition and free markets created opportunities for some. But it also built inequality deeply into the system—something that continues to shape the country today.

In Summary: While Reagan is often credited as the architect of neoliberalism in the U.S., presidents from Truman to Carter had already moved the country in that direction through a mix of deregulation, tax policies, and weakened labor protections. These actions collectively paved the way for Reagan’s more aggressive dismantling of the New Deal consensus.

Neoliberalism has many faces in history. Is it new??

The story is about an inverted order. The earth was for everyone's sustenance. Austerity consumes. A rationalism that impoverishes.

Adam Smith developed the economic law-based approach in The Wealth of Nations in 1776, the same year the United States was founded.

He became the father of the hypothetical laws of the free market economy that were established and the idea of automatic self-equalization. Smith explained the revolutionary principle that society benefits from the selfishness of the individual, and thus laid the foundation for the entire economic liberalism.

Society consists of the people and the economy assists in the well-being of the people in building society and the national economy for the common good. An interpersonal event in a human unity. Everything resembles a tree where

* the public is the common trunk to distribute the wealth in care, school, roads, communism, etc.

* the private are the branches with their useful purposes and necessities.

They exist to provide for and develop the nation socially, culturally and economically through work.

The ability to create together is called civility. High civility is peace, togetherness and unity.

Culture here consists of spreading light and knowledge through research, the artistic, developing customs, language and norms that unite. All of this expresses a creation, which is part of a larger universal creation.

Economy is no longer in tune with the earth. Climate and environmental problems are generated by human economy. Societies are being torn apart. The economist of greed rules in an unscrupulous group. The representatives are reshaping laws and social institutions to pave the way for the new law and order

Reality is being simplified.

What is not seen simply does not exist and is treated as something irrational. The entire yardstick and ethics are limited to material values in money or the tax table. Context, purpose and purpose are lost.

Without values in justice there is no compass direction.

In 1932, upon his Democratic nomination, Franklin Roosevelt promised “a new deal for the American people. He speaks for the people and that is the way to the solution.

The conclusion is still true today.

“The whole nation, all men and women, are forgotten in the political philosophy of the present government. They look to us here for guidance and for a fairer opportunity to share in the distribution of the national wealth… I pledge myself to a new deal for the American people. This is more than a political campaign. It is a call to arms.

We shouldn't forget the material groundwork. New Deal built on industrial capitalism, but industrial capitalism got into trouble in the 60s-70s, by its sheer effectiveness. It produced more than there was effective demand for; it got into an overproduction crisis and had to turn to the finance market for help.

And the finance markets is equal to rentiers, rich dilettantes who are uninterested in production and investments but only want quick return on their money. So the industrial giants fired the CEOs who wanted production and put in CEOs who speculated in assets instead. Which is the core of neoliberalism.

If you want an inflection point, 1968 is a good one. It was then RCA, the radio giant, stopped investing in future product development and began buying any kind of profitable business instead, for example Hertz. It was called "diversification". Within a decade, RCA was gone.